Passover summons stories

This week is Passover, the Jewish festival remembering the Hebrews’ Exodus from Egypt. Have you ever watched the Charlton Heston film where the actor plays the Prophet, Moses? No? Well, I’ll save you three hours of your life and advise you, only watch it if you’re looking for a cure for your insomnia.

I’m being unfair. It’s a classic film, about a classical biblical story…

A story, I’m always struck, that continues to get shared in Jewish households at least three millennia after (the Old Testament at least) suggests the historic events of Moses and the Hebrews’ exodus from the Pharaoh and slavery occurred.

A story, I’m always struck, that continues to get shared in Jewish households at least three millennia after (the Old Testament at least) suggests the historic events of Moses and the Hebrews’ exodus from the Pharaoh and slavery occurred.

Reading the Haggadah, the prayer book used for Passover services, I was struck by some of the images of previous generations – sketched in communal celebration and prayer.

There were images of previous generations marking the Passover festivities, eating their Matzah bread, and commemorating events so abstract, it’s extraordinary to think of their indelible imprint not just now, but in recent periods of history when Jewish families still gathered in secret, discreetly at least, against the growing drumbeat of Fascism and Hitler’s rise to power.

I participated in an online service for LGBT+ Jews last night. I loved Rabbi Roderick Young’s zest for storytelling. Rabbi Roderick regaled us with the stories of Moroccan Jews who hand plates of Matzah bread over their heads to represent the affliction our forebears experienced under the conditions of building the pyramids.

He also shared a story that I must admit if I’d ever heard it, I’d forgotten. In fact, it’s not a story so much, but rather an interpretation of the Passover story as told by debating rabbis (of course, who else?).

Remembering the tragic, not just celebrating the joy

In brief, the story goes as follows: after G-d let the Red Sea part for Moses and the Hebrews, escaping Rameses’ vengeful army, (he/she/G-d) commanded the angels to stop their singing. They weren’t to celebrate, for G-d had to briefly allow misery to provide safety and sanctuary for his people. Many Egyptians died; there was nothing to be celebratory about. This is why we don’t lick the wine from the fingers we dab ten times – we take ten drops of wine from our cups to represent the ten plagues that befell the Pharaoh and the Egyptians. But once we’ve dabbed these ten droplets on our saucers or plates, we must leave it at that.

We don’t lick our fingertips, Rabbi Roderick advised us, not because we’re living in a Pandemic, although that might be one temporary hygienic benefit to not doing so, but because we mustn’t treat the Egyptians’ fate – the ten plagues G-d tested them with – as anything but joyous. The Hebrews’ escape from serfdom – the birth of ‘Israel’ in an ancient sense – is but one twist in the Jewish people’s five-millennia survival story.

We don’t lick our fingertips, Rabbi Roderick advised us, not because we’re living in a Pandemic, although that might be one temporary hygienic benefit to not doing so, but because we mustn’t treat the Egyptians’ fate – the ten plagues G-d tested them with – as anything but joyous. The Hebrews’ escape from serfdom – the birth of ‘Israel’ in an ancient sense – is but one twist in the Jewish people’s five-millennia survival story.

But it’s not a story without consequences, and Passover is a festival to both genuinely celebrate, and feel joyous about, but one where we must remember all previous generations’ pain, and the pain that continues for oppressed peoples around the world today. We called for greater recognition and action to address the needs of the Uighur Muslims in North West China and the Rohingya Muslims forced as refugees to camp in or try to survive in Bangladesh.

Hidden Histories

Another Passover Seder night passes, and the riches of stories continues to amaze me.

In many ways, Passover is a festival of storytelling. Above all, it seems to summon our collective spirit to look beyond our immediate condition, our parochial position in the world, and to fight for justice for all those, who like the Hebrews, face injustice now. We can cite the stories of the Uighur and the Rohingya people, but there are the Palestinian people in the Occupied Territories, and countless other stories we could highlight of people facing oppression now.

In previous blogs, I’ve written about why I personally feel marking history, not forgetting, and continuing to tell our stories, is so important. Why recognising the collective complexity of all our stories: people of faith and people of no faith, is so meaningful and cathartic, and yes, socially responsible too.

I’ve also started blogging as part of a new spring season of blog-posts on the joys and complications of my Jewish background and identity.

And so to this week’s blog: the hidden histories we must continue revealing, excavating even, for many remain well-concealed.

The Lithuanian connection

In my last blog, I shared some personal news. I’ve decided to change my family name from Kaye to Kaufman: to reclaim my family’s Ashkenazi roots and de-anglicise the name, if I could put it like that. Put it like this, it’s not so hidden now.

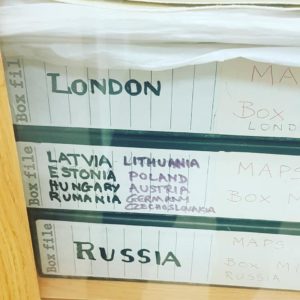

I wrote about my family from Sakiai in what is now south west Lithuania.

Earlier this month, I participated in Jewish Book Week. One of the online events I was drawn to attend was on ‘Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust‘. Yes, I’m a bundle of joy – a laugh a minute.

Earlier this month, I participated in Jewish Book Week. One of the online events I was drawn to attend was on ‘Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust‘. Yes, I’m a bundle of joy – a laugh a minute.

Boy, was this a hidden history.

Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust

Ruta Vanagaite, a best-selling Lithuanian writer and a descendant of Lithuanian perpetrators of the Holocaust has written a book called ‘Our People: Discovering Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust‘. Listening to her and co-author, Efraim Zuroff, a noted Nazi-hunter, left me moved. Goosebumps, certainly, and tingling.

In a matter-of-fact way, Ruta posited that for approximately 200,000 Jews to have been murdered during the Soviet and then the Nazi occupation in Lithuania, and since not that many Nazis were stationed in the country relative to the Jewish population (possibly 600-900), ordinary Lithuanian people must have been complicit – must in some cases have themselves murdered their Jewish compatriots and neighbours.

In a matter-of-fact way, Ruta posited that for approximately 200,000 Jews to have been murdered during the Soviet and then the Nazi occupation in Lithuania, and since not that many Nazis were stationed in the country relative to the Jewish population (possibly 600-900), ordinary Lithuanian people must have been complicit – must in some cases have themselves murdered their Jewish compatriots and neighbours.

Here were some of the key things she claimed, based on extensive research:

- There were over 230 mass murder sites in Lithuania, nearly all in the forest

- It was clear from the beginning of Lithuanian independence in the early 1990s, there was a narrative that the Holocaust didn’t take place in the country. There was a concerted attempt to suppress any real recollections of Lithuanians’ collaboration

There are around 2,000-3,000 Jews left in Lithuania today, remarkable when we consider the pre-World War Two ‘Litvak’ population. The 2005 Census counted 2,000 Jewish people in Lithuania. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population.[see link to Wikipedia] Vilnius had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city’s total population.[see link to Wikipedia]

There are around 2,000-3,000 Jews left in Lithuania today, remarkable when we consider the pre-World War Two ‘Litvak’ population. The 2005 Census counted 2,000 Jewish people in Lithuania. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population.[see link to Wikipedia] Vilnius had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city’s total population.[see link to Wikipedia] - If you mention the word “Jew” in Lithuania today, and certainly the Holocaust, people’s faces turn to stone

- When she was a child, there was a playground game in which a ‘Jew’ climbs a ladder and when they descend, the other children would ‘murder’ the child playing the role of the ‘Jew’

- A narrative took hold among the Lithuanian populace that the Soviet invasion was the fault of Jews, that they deserved their fate, but this is historically fallacious, as well as downright racist, because by the time Stalin was in power, there were few Jews in his NKVD / secret police force

She continued, again a witness to history insomuch as she didn’t ever see her family acknowledging its own complexities, its own complicity perhaps in some of Lithuania’s dark history. She talked about:

- The evolving history of Lithuania’s Holocaust was especially upsetting because pre-War there was less of a cultural history of anti Semitism than in Poland or Hungary, say. In fact, dating back to 1388, a royal figure in Lithuanian said it was a social duty to help a Jew in distress (a rare example in medieval Christian Europe). There were hardly any pogroms against the Jews in Lithuania, unlike in Russia – possibly around ten in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, so again, ordinary people’s collaboration in the Nazi Holocaust was especially shocking

- The 3,000 approx. Lithuanian Jews saved or aided during the War, or who survived the camps. Ten to fifteen books have been published in Lithuania on ordinary Lithuanians who were ‘righteous among the nations’, people who saved Jews. No book until Ruta Vanagaite’s book has tackled the sensitive and difficult subject of Lithuanians who collaborated or themselves committed murderous acts. She refers to the summer of 1941, after Operation Barbarossa: “the villages were murdered, totally”.

There are exceptions to every rule, every story has its nuances

There are accounts of Priests who saved Lithuanian Jews.

Some Georgian Jews, some Jews in Uzbekistan and some Karaim Jews, who were originally of Tatar ethnicity, were either treated as Prisoners of War or spared.

Of course countless numbers of Lithuanian civilians (as well as soldiers) died in World War Two. Estimates are very imprecise and range dramatically owing in part due to the lack of authoritative census data covering the period. When the Nazis attacked the capital, Vilnius, after they broke their pact with Stalin and the Soviets in June 1941, at least 4,000 civilians died in the first weeks of the Nazi occupation.

Of course countless numbers of Lithuanian civilians (as well as soldiers) died in World War Two. Estimates are very imprecise and range dramatically owing in part due to the lack of authoritative census data covering the period. When the Nazis attacked the capital, Vilnius, after they broke their pact with Stalin and the Soviets in June 1941, at least 4,000 civilians died in the first weeks of the Nazi occupation.

But the central point Ruta Vanagaite, Lithuanian and non-Jew, makes is that the Jews were killed in such extraordinary numbers, a number so unprecedented, Lithuanians too must have been involved, together with the Nazis. The genocide rate of Jews in Lithuania, recorded up to 95–97%, was one of the highest in Europe, sources are quoted reporting.

Reflecting for my family, for all Lithuanians

As I was listening to Ruta, I reflected on my own family. Tobias Finn and one of his descendants, Joseph Finn, who came from a small town near the Lithuanian city of Kaunas.

Like many ‘Litvaks’ who emigrated in the late nineteenth century, perhaps most of all to the United States, they fled poverty as much as they fled the pogroms. My family didn’t remain in Lithuania. They were among the lucky ones.

Ruta had to go to extraordinary lengths to write this book. While obsessing about the question, “how does a peaceful peasantry rise up and kill its neighbours?”, she’s had to revisit some dark family secrets.

Ruta had to go to extraordinary lengths to write this book. While obsessing about the question, “how does a peaceful peasantry rise up and kill its neighbours?”, she’s had to revisit some dark family secrets.

She pointed out the “we tend to think only some ‘degenerates are real Holocaust perpetrators,” but then added, “that’s wrong. My aunt’s husband wasn’t himself shooting Jews, but neither was Adolf Eichmann (a leading Nazi)”. She’s had to bust the myth that the Nazis did everything themselves; that culpability can cleanly be apportioned to some people, and not others.

Co-author Efraim Zuroff interviewed an older Lithuanian for the book. There’s a sense growing life expectancies have allowed researchers to have a last ‘go’ at interviewing witnesses, but nevertheless, many of the last survivors who remember living through the Holocaust as young adults, and certainly many of the perpetrators, are dying. Zuroff asked his interviewee – a non-Jew – if she’d been afraid of the Germans. She responded, “no, we were afraid of our neighbours.”

Lithuania changing?

Vanagaite suggests that some things in Lithuania are changing. Nevertheless some in Lithuania have accused her of being one of ‘Putin’s agents’, wanting to discredit Lithuania. The government narrative on its recent history can sometimes still be faulty, but then, positively, Vanagaite points to an open letter than seventeen historians wrote to the government, openly accusing them of getting their facts wrong. I don’t believe they were punished or anything like that.

Vanagaite suggests that some things in Lithuania are changing. Nevertheless some in Lithuania have accused her of being one of ‘Putin’s agents’, wanting to discredit Lithuania. The government narrative on its recent history can sometimes still be faulty, but then, positively, Vanagaite points to an open letter than seventeen historians wrote to the government, openly accusing them of getting their facts wrong. I don’t believe they were punished or anything like that.

2,000 copies of Our People: Discovering Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust were printed, but the book sold out in Lithuania within 48 hours. Vanagaite said in the online event: “The Holocaust in Lithuania will never be ‘nothing’, like it was for 75 years”.

I visited Vilnius one March weekend, four years ago. It’s a charming city. It bears some of the hallmarks of its pre-War and wartime Jewish heritage, but none of the synagogues erected before the war still stand in their place today. The closest I came to seeing one of the old synagogues was a playground with rusting swings, standing above its long forgotten stone remnants.

The haunting call of our hidden histories

I tell this story not because it’s particularly satisfying or rewarding in its own right, but because each history has its own significance, its own value and meaning.

I’ve written about how any people that forgets its past risks being condemned to repeat it.

This doesn’t mean we must obsess about our past, or fail to move beyond historic associations of victimhood, blame and retribution. History should teach us things, neither be a fading photograph, nor an albatross around our necks.

I liked the fact that when I visited Vilnius I could visit a museum on the Holocaust, difficult though it was to visit it. I liked the smoked salmon bagels I picked up and joyously ate from a kosher bakery.

When I visited Lviv in Ukraine, in October 2019, I was disappointed not to see the Golden Rose synagogue, since what lies in its place today are memorial stones to the city’s murdered Jews, not a tapestry depicting Moses’ atop Mount Sinai, nor any Haggadah books inside for the city’s Jewish congregants to celebrate the annual Passover. But I visited a quirky museum of the city’s (mainly hidden) Jewish past, and Philippe Sands’ towering piece of research, published as East West Street, helped me to join any remaining dots.

When I visited Lviv in Ukraine, in October 2019, I was disappointed not to see the Golden Rose synagogue, since what lies in its place today are memorial stones to the city’s murdered Jews, not a tapestry depicting Moses’ atop Mount Sinai, nor any Haggadah books inside for the city’s Jewish congregants to celebrate the annual Passover. But I visited a quirky museum of the city’s (mainly hidden) Jewish past, and Philippe Sands’ towering piece of research, published as East West Street, helped me to join any remaining dots.

Whatever (or whomever) we lose, we must lament and later mourn, commemorate and acknowledge. Whatever lessons history teaches us, let’s at least agree, there are lessons that need to be learnt, that we can’t let our histories simply fade.